Berkshire Hathaway, which has created countless legends under Warren Buffett’s leadership, will finally step down as CEO at the end of this year, officially retiring from day-to-day operations. He released his final annual shareholder letter yesterday.

(Background: Buffett admitted: I really feel old, thinking and reading are becoming increasingly difficult… First time discussing his decision to step down as Berkshire CEO )

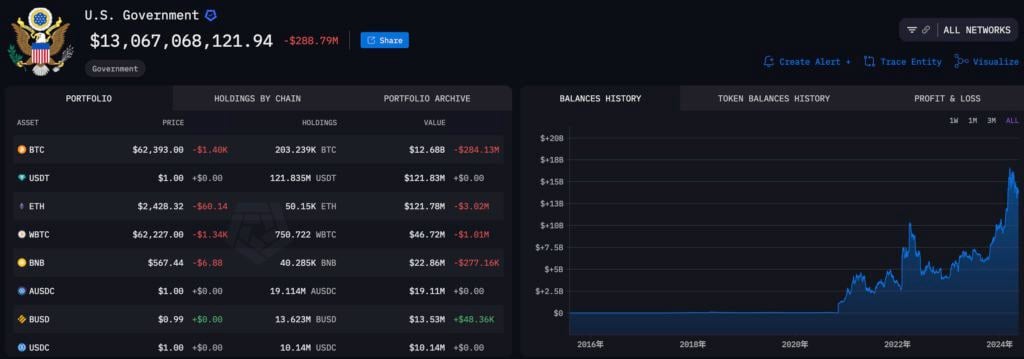

(Additional background: Buffett invested in the Brazilian cryptocurrency-friendly bank Nu Holdings, with Berkshire Hathaway holdings amounting to 1.2 billion magnesium .)

![图片[1]-Warren Buffett’s final letter to shareholders: Live the life you want to be remembered, and bid farewell after 60 years at the helm of Berkshire Hathaway.-OzABC](https://www.ozabc.com/wp-content/uploads/buffet-750x375-1.webp)

shareWarren Buffett has led Berkshire Hathaway for over 60 years since 1965, delivering substantial returns and inspiration to shareholders and global investors. On Monday (October 10th), Buffett officially wrote his final annual letter to shareholders, reiterating his intention to step down as CEO at the end of the year.

The following is a translation of the entire shareholder letter from [website name – likely a translation platform].

To my shareholders:

I will no longer write Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report, nor will I speak at length at the annual shareholders’ meeting. As the British say, I am “becoming quieter.”

I guess so.

Greg Abel will become the boss at the end of the year. He is an excellent manager, a tireless worker, and an honest communicator. Wishing him a long and successful tenure.

I will continue to talk to you and my children about Berkshire Hathaway through my annual Thanksgiving message. Berkshire’s individual shareholders are a very special group; they are exceptionally generous in sharing their profits with those less fortunate. I enjoy staying in touch with you. Please allow me to start this year with a few reflections. Afterward, I will discuss my Berkshire Hathaway share allocation plan. Finally, I will offer some insights on business and personal matters.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

As Thanksgiving approaches, I am grateful and am surprised that I have the privilege of living to be 95 years old.

When I was young, this outcome didn’t seem so certain. I almost died early in my life.

That was in 1938, and hospitals in Omaha were perceived by the public as either Catholic or Protestant, a classification that seemed natural at the time.

Our family doctor, Harley Hotz, was a friendly Catholic who would come to our house carrying a black bag. Dr. Hotz called me “Skipper,” and his fees were never high. In 1938, when I was in severe abdominal pain, Dr. Hotz came, examined me, and told me I would be fine by morning.

Then he went home, had dinner, and played some bridge. However, Dr. Hotz couldn’t forget my somewhat peculiar symptoms, and later that evening he took me to St. Catherine’s Hospital for an emergency appendectomy. For the next three weeks, I felt like I was in a convent and began to enjoy my new “preaching platform.” I loved to talk—yes, even then—and the nuns were very welcoming.

What’s more, my third-grade teacher, Miss Madsen, told me that each of my 30 classmates wrote me a letter. I probably lost all the letters the boys wrote, but I read the girls’ letters over and over again; even hospitalization has its rewards.

A highlight of my recovery process—which was actually quite dangerous for most of the first week—was a gift from my lovely Aunt Edie. She brought me a very professional-looking fingerprinting kit, and I immediately had my fingerprints taken from all the nuns who cared for me. (I was probably the first Protestant child they saw at St. Catherine’s Hospital, and they had no idea what was going to happen.)

My theory—which was, of course, utterly insane—was that one day a nun would turn bad, and the FBI would discover they had neglected to collect her fingerprints. The FBI and its director, J. Edgar Hoover, were respected by Americans in the 1930s, and I imagined Mr. Hoover himself coming to Omaha to examine my precious collection. I further fantasized that J. Edgar and I would swiftly identify and arrest that capricious nun. National fame seemed imminent.

Obviously, my fantasy never came true. Ironically, however, years later it turned out I should have collected J. Edgar’s own fingerprints, as he later became infamous for abusing his power.

Yes, this is Omaha in the 1930s, when my friends and I longed for a sled, a bicycle, a baseball glove, and an electric train. Let’s look at a few other kids from that era who grew up nearby and had a huge impact on my life, but whom I didn’t know for a long time.

I’ll start with Charlie Munger, my best friend of 64 years. In the 1930s, Charlie lived just one block away from the house I’ve owned and lived in since 1958.

I almost became friends with Charlie in my early years. Charlie was 6 and 15 years older than me and worked at my grandfather’s grocery store in the summer of 1940, working 10 hours a day for $2. (The virtue of thrift is in Buffett’s blood.) The following year, I did a similar job at the store, but I didn’t meet Charlie until 1959, when he was 35 and I was 28.

After serving in World War II, Charlie graduated from Harvard Law School and then moved permanently to California. However, Charlie always said that his early years in Omaha were crucial to the formation of his character.

Charlie has had a tremendous influence on me for over 60 years. He has been the best teacher and the most protective “big brother” I could ever have. We have disagreements, but we’ve never argued. “I already told you that” is not in his vocabulary.

In 1958, I bought my first and only house. Of course, it was in Omaha, about two miles from where I grew up (in a broad sense), less than two blocks from my in-laws’ house, about six blocks from Buffett’s grocery store, and a 6-7 minute drive from the office building where I worked for 64 years.

Let’s move on to another Omaha man, Stan Lipsey. Stan sold the Omaha Sun (a weekly newspaper) to Berkshire Hathaway in 1968 and moved to Buffalo ten years later at my request. The Buffalo Evening News, owned by a Berkshire affiliate, was then locked in a fierce battle with its morning rival, which published Buffalo’s only Sunday newspaper. And we were losing ground.

Stan eventually built our new Sunday product, and in some years, our previously heavily loss-making newspaper earned over 100% annual (pre-tax) returns on our $33 million investment. That was a significant sum for Berkshire in the early 1980s.

Stan grew up about five blocks from my house. One of Stan’s neighbors was Walter Scott, Jr. You’ll remember that Walter brought MidAmerican Energy to Berkshire in 1999. He was a highly respected board member of Berkshire until his death in 2021, and also a very close friend. For decades, Walter was a philanthropic leader in Nebraska, and his mark is felt throughout Omaha and the state.

Walter attended Benson High School, and I had planned to go there too—until 1942 when my father surprised everyone by defeating a four-term incumbent congressman in the general election. Life is full of surprises.

Wait, there’s more.

In 1959, Don Keough and his young family lived in the house directly across from mine, about 100 yards from where the Munger family had lived. Don was a coffee salesman at the time, but was destined to become the president of Coca-Cola and a loyal director of Berkshire Hathaway.

When I met Tang, he earned $12,000 a year and was raising five children with his wife, Mickie, all of whom were destined to attend Catholic schools (which required tuition).

Our families quickly became friends. Don came from a farm in northwestern Iowa and graduated from Creighton University in Omaha. He married Midge, an Omaha girl, early in his life. After joining Coca-Cola, Don became known worldwide.

In 1985, when Don Reed was president of Coca-Cola, the company launched the ill-fated “New Coke.” Reed delivered a famous speech apologizing to the public and reverting to the “old Coke.” This shift came after Reed explained that letters addressed to Coca-Cola with “Supreme Idiot” written on them were being rapidly delivered to his desk. His “retraction” speech is considered classic and can be viewed on YouTube. He happily acknowledged that, in fact, Coca-Cola products belonged to the public, not the company. Sales subsequently soared.

You can watch a great interview with Don at CharlieRose.com. (Tom Murphy and Kay Graham also have some great segments.) Like Charlie Munger, Don Forever is a Midwestern boy—warm, friendly, and a true American at heart.

Finally, Ajit Jain, who was born and raised in India, and our incoming Canadian CEO, Greg Abel, both lived in Omaha for a few years in the late 20th century. In fact, Greg lived on Farnam Street, just a few blocks from my home, in the 1990s, although we never met at the time.

Is there some magical ingredient in the water of Omaha?

* * * * * * * * * * * *

I spent several years of my teenage years in Washington, D.C. (where my father was in Congress), and in 1954, I found what I thought would be a permanent job in Manhattan. There, Ben Graham and Jerry Newman treated me exceptionally well, and I made many lifelong friends. New York has a unique asset—and still does. Nevertheless, in 1956, just a year and a half later, I returned to Omaha and never wandered again.

Subsequently, my three children and several grandchildren were raised in Omaha. My children attended public schools throughout their education (the high school they graduated from also educated my father (class of 1921), my first wife Susie (class of 1950), as well as Charlie, Stan Lipsey, Irv and Ron Blumkin, who were crucial to the development of the Nebraska Furniture Mart, and Jack Ringwalt (class of 1923), who founded National Indemnity and sold it to Berkshire Hathaway in 1967, which later became the foundation of our large property and casualty (P/C) insurance business.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Our country has many great companies, great schools, and great healthcare facilities, each with its own unique strengths and talented people. But I feel incredibly fortunate to have made so many lifelong friends, met both my wives, received a wonderful early education in public schools, encountered so many interesting and friendly adults in Omaha at a young age, and made a diverse group of friends in the Nebraska National Guard. In short, Nebraska has always been my home.

Looking back, I think Berkshire Hathaway and I both did better because we were based in Omaha than I would have anywhere else. The heart of America is a great place to be born, raise a family, and start a business. By sheer luck, I was born with an absurdly long lottery ticket.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Now let’s talk about my advanced age. My genes haven’t been particularly helpful—before I came along, the family’s longevity record (admittedly, the further back in the family record goes, the less clear it becomes) was 92. But I’ve had wise, kind, and dedicated doctors in Omaha, from Harry Hotz to this day. My life has been saved at least three times, each time by doctors within miles of my home. (Though, I’ve given up on taking nurses’ fingerprints. You can do a lot of weird things at 95… but everything has its limits.)

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Those who live to old age need immense good fortune, having to dodge banana peels, natural disasters, drunk or distracted drivers, lightning strikes—you name it.

But Lady Luck is fickle—no other word fits it better—and utterly unfair. In many cases, our leaders and the wealthy receive far more good fortune than they deserve—and those who receive it are often unwilling to admit it. Heirs to dynasties are born with lifelong financial independence, while others face hellish lives from birth, or worse, physical or mental disabilities that rob them of what I take for granted. In many densely populated parts of the world, my life is likely to be miserable, and my sisters’ lives will be even worse.

I was born in the United States in 1930, healthy, of average intelligence, white, male. Wow! Thank you, Lady Luck. My sisters possessed the same intelligence as me, and their personalities were even better, but their futures were drastically different. For most of my life, Lady Luck smiled upon me, but she had more important things to do than favor someone in their nineties. Luck is finite.

Conversely, Father Time finds me more interesting now that I’m getting older. He’s invincible; to him, everyone ultimately becomes a “victory” on his scorecard. When your balance, eyesight, hearing, and memory all continue to decline, you know Father Time is nearby.

I started getting old relatively late—the timing of aging varies from person to person—but once it begins, it cannot be denied.

To my surprise, I generally feel good. Although I’m moving slowly and reading is becoming increasingly difficult, I still spend five days a week in the office working with excellent people. Occasionally, I’ll come up with a useful idea or receive a quote we might not otherwise have received. Given Berkshire’s size and market level, ideas are few—but not zero.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

However, my unexpected longevity has had an unavoidable and significant impact on my family and the achievement of my philanthropic goals.

Let’s discuss this.

What’s next?

My children are all past the normal retirement age, at 72, 70, and 67 respectively. It would be a mistake to bet that all three of them—currently at their peak in many ways—will be as fortunate as I am to delay aging. To increase the likelihood that they will dispose of essentially my entire estate before a successor takes over, I need to accelerate the process of making lifetime donations to their three foundations. My children are currently at the peak of their experience and wisdom, but have not yet entered old age. That “honeymoon period” will not last forever.

Fortunately, the revised course is easy to implement. However, there is one additional factor to consider: I want to retain a significant amount of “A” stock until Berkshire shareholders develop the same level of confidence in Greg that Charlie and I have long enjoyed. This level of confidence shouldn’t take long. My children are 100% supportive of Greg, and so are the Berkshire board members.

My three children now possess the maturity, wisdom, energy, and intuition to allocate such a vast fortune. They will also have the advantage of being alive long after I’m gone, and being able to implement proactive and reactive policies, if necessary, to address federal tax policies or other developments affecting philanthropy. They will likely need to adapt to a world undergoing significant changes. My track record of “ruling from the grave” is poor, and I have never felt the urge to do so.

Fortunately, all three children inherited the dominant gene from their mother. Over the decades, I have also become a better role model for them in terms of thought and behavior. However, I can never compare to their mother.

My children have three alternative trustees in case of any premature death or incapacity. These trustees are not ranked and are not tied to any particular child. All three are outstanding and worldly-wise individuals. They have no conflict of interest.

I have assured my children that they do not need to perform miracles, nor should they be afraid of failure or disappointment. These are inevitable, and I myself have made my share of mistakes. They simply need to make slight improvements on what government activities and/or private philanthropy typically achieve, while recognizing that these other methods of wealth redistribution also have their drawbacks.

Earlier in my life, I had considered various grand philanthropic projects. Though I was stubborn, these projects proved unworkable. Over the years, I have also witnessed political hacking, dynastic choices, and, yes, poorly conceived wealth transfers by incompetent or eccentric philanthropists.

If my children do well, they can be sure their mother and I will be very happy. They have excellent intuition, and they have each practiced for many years, starting with very small amounts and increasing irregularly to over $500 million annually now.

All three of them enjoy working long hours to help others, each in their own way.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

My accelerated lifetime donations to the Children’s Foundation do not reflect any change in my view of Berkshire’s future. Greg Abel has exceeded the high expectations I had for him when I initially thought he should be Berkshire’s next CEO. He knows far more about our business and people than I do now, and he learns remarkably quickly about things that many CEOs haven’t even considered. I can’t think of any CEO, management consultant, academic, or government official—name your name—whom I would choose instead of Greg to manage our savings.

For example, Gregg’s understanding of the upside potential and risks of our property and casualty (P/C) business far surpasses that of many seasoned P/C executives. I hope his health remains good for the next few decades. With luck, Berkshire should only need five or six CEOs in the next century. It should especially avoid those whose goal is to retire at 65, become “look-at-me rich,” or establish a dynasty.

An unpleasant reality is that occasionally, an excellent and loyal CEO of a parent company or subsidiary may suffer from dementia, Alzheimer’s, or other debilitating long-term illnesses. Charlie and I have encountered this problem several times and failed to act. This oversight could be a huge mistake. Boards must be vigilant about the possibility of this happening at the CEO level, and CEOs must be vigilant about the possibility of this happening at the subsidiary level. This is easier said than done; I could cite examples from some large companies in the past. My advice is simply that boards should be vigilant and speak out.

In my lifetime, reformers attempted to humiliate CEOs by demanding the disclosure of salary comparisons between bosses and ordinary employees . Proxy statements quickly ballooned to over 100 pages, whereas earlier they were only 20 pages or less.

But good intentions didn’t work; they backfired. Based on much of my observation—Company A’s CEO looked at Company B’s competitors and subtly conveyed to the board that he deserved higher compensation. Of course, he also increased director salaries and carefully selected members for the compensation committee. The new rules fostered envy, not restraint.

This ratcheting effect has taken hold. What truly plagues very wealthy CEOs—after all, they are human—is the fact that other CEOs are becoming even wealthier. Envy and greed go hand in hand. And which advisor has ever suggested drastically cutting CEO compensation or board fees?

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Overall, Berkshire’s business outlook is slightly better than average, led by a few unrelated but sizable gems. However, in ten or twenty years, many companies will be doing better than Berkshire; our size is becoming a drag.

The odds of Berkshire experiencing a devastating catastrophe are lower than any other business I know. Furthermore, Berkshire’s management and board are more shareholder-conscious than almost any company I’ve been familiar with (and seen many of). Ultimately, Berkshire’s management style will forever make its existence an asset to America and avoid the activities that would turn it into a pleader. Over time, our managers should become quite wealthy—they bear significant responsibilities—but they lack the desire to build a dynasty or the “look how rich I am” mentality.

Our stock price will be volatile, occasionally dropping by around 50%, just as it has happened three times in the 60 years under the current management. Don’t despair; America will return, and Berkshire’s stock will return.

Some final thoughts

One observation, perhaps selfishly. I’m happy to say I feel better about the second half of my life than the first. My advice is: don’t blame yourself for past mistakes—at least learn something from them and move on. It’s never too late to improve. Find the right heroes and emulate them. You can start with Tom Murphy; he’s the best.

It is said that Alfred Nobel, the later founder of the Nobel Prize, read his own obituary, which had been mistakenly published by the newspapers when his brother died. He was shocked by what he read and realized that he should change his behavior.

Don’t expect the newsroom to get confused: decide how you want your obituary to be written, and live a life worthy of that writing.

Greatness doesn’t come from accumulating vast sums of money, immense fame, or powerful positions in government. When you help others in any of the thousands of ways, you are helping the world. Kindness has no cost, yet it is priceless. Whether you are religious or not, it’s hard to find a better code of conduct than the Golden Rule.

I’m writing this as someone who has made countless mistakes and lacked foresight, but has also been fortunate enough to learn how to do better (though I’m far from perfect) from some wonderful friends. Please remember, cleaning ladies and CEOs are both human.